It took a while for LeeAnne Walters to realize the full impact of the number: 13,200.

Walters—a stay-at home mom with four sons and a husband in the Navy—had seen other numbers reflecting the quality of drinking water at her Flint home that were devastating. But 13,200? She’d never seen anything like this.

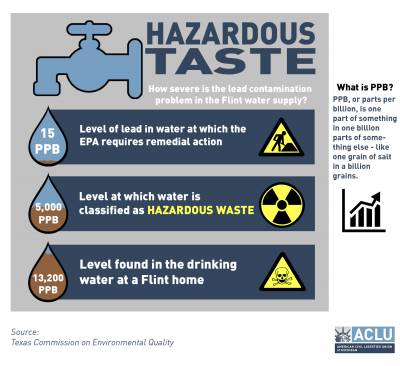

The city had tested her water twice in this past March and both times found dangerously high levels of lead—104 parts per billion (ppb) and 397 ppb, respectively.

Those numbers filled her with dread, because they meant her family had been exposed to high levels of a terribly toxic heavy metal that put her children’s future in jeopardy.

But it was the result of a third test of the tap water in her home, performed by independent experts at Virginia Tech university, that most stunned Walters.

“It took a while for me to wrap my head around it,” said Walters.

The VT researchers discovered lead levels in Walters’ water reached a jaw-dropping 13,200 ppb—more than twice the amount at which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency classifies water as hazardous waste.

“When I saw those numbers I was shocked,” said Virginia Tech professor Marc Edwards, a former MacArthur Fellow and respected authority on corrosion in drinking-water systems, who oversaw the tests.

Edwards played a key role in discovering the problem of corroded water pipes and lead in Washington, D.C. drinking water during the early 2000s, in what has been described as one of the worst contamination events ever seen in an urban water system, with resulting increased incidence of childhood lead poisoning, miscarriages and fetal death.

In terms of lead levels, the Walters family’s numbers eclipsed even the worst D.C. homes.

“I have never in my 25-year career seen such outrageously high levels going into another home in the United States,” said Edwards. “This was literally hazardous-waste levels.”

But the condition of Walters’ tap water raises a much more far-reaching question: Since the city moved away from Detroit’s water system and began pumping water from the Flint River, how many other families have been put at risk by the city’s questionable testing procedures and handling of the water supply?

The Walters family surely isn’t alone in dealing with the threat of lead-laced drinking water. About half of Flint’s 40,000 homes are a half-century old or older, built at a time when water service lines were typically made of lead.

And according to various experts, including an EPA water-quality specialist, the city’s actions are only exacerbating the threat.

“What the public needs is accurate information,” explained Miguel Del Toral, regulations manager for the Ground Water and Drinking Water Branch of the EPA’s Region 5.

Instead, the city is utilizing testing measures that almost ensure that worst-case scenarios such as the one facing the Walters family escape detection, asserted Del Toral in an internal EPA memo provided to the ACLU of Michigan.

Compounding the threat is what Del Toral describes as the continued inability of officials to adequately treat water coming into people’s homes from the Flint River.

“I don’t want to scare people unnecessarily,” said Del Toral in a phone interview from his home in Chicago. “But there is absolutely a problem in Flint that needs to be addressed right away.”

During his interview with the ACLU of Michigan, Del Toral said he was willing to go on the record with his concerns, but that he was doing so as a private citizen, not as a representative of the EPA.

EPA rules, he said, required that such interviews be routed through the agency’s public affairs people. But he’s willing to speak out nonetheless, he said, because of the potential harm to the public is so great, and the need to address it is so urgent.

WATERING DOWN THE TESTS

Perhaps the most vexing problem in all of this is the contamination caused by the city’s decades-old network of lead and iron pipes—a problem directly connected to the switch to river water, and the city’s failure to adequately treat it.

Under the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s rules, if lead reaches a level of 15 parts per billion in water, the source of the problem must be identified and corrected.

In early March, after months of requests (and only after Walters had received a doctor’s note raising concerns about problems with the water), the city finally conducted a test. It found lead levels of 104 ppb the first time. A second test recorded a level of 397 ppb.

Blood tests, taken after those water-sample numbers were reported, revealed that one of her children, a four year old, had lead poisoning.

The news was devastating, said Walters, and the concern it creates for her child’s future is haunting.

“Lead can affect almost every organ and system in your body,” according to the EPA’s web site. “Children six years old and younger are most susceptible … Even low levels of lead in the blood of children can result in: behavior and learning problems; lower IQ and hyperactivity; slowed growth; and hearing problems.”

Those dangers made Walters all the more determined to get her questions answered.

For one thing, she wanted to know why residents were being instructed to “pre-flush” water lines before drawing samples that would be tested by the city

After much searching, she found Del Toral at the EPA’s Region 5 in Chicago. He explained to her that her instincts were right, and that she had good cause to be concerned about the way testing was being done.

“The practice of pre-flushing before collecting compliance samples has been shown to result in the minimization of lead capture and significant underestimation of lead levels in drinking water,” wrote Del Toral in an internal memo dated June 24.

Del Toral went on to say that the city’s testing methods were a “serious concern” because they “could provide a false sense of security to the residents of Flint regarding lead levels in the water.” As a result, he warned, residents could fail to take the necessary precautions to protect their families from lead in the drinking water.

Virginia Tech’s Edwards completely agrees with Del Toral’s assessment.

“The net effect of a ‘pre-flush’ is to greatly reduce the likelihood of detecting lead in samples collected … that would normally be present in the consumers drinking water,” Edwards wrote in an email. “I have long maintained that the practice should be banned, as it artificially lowers the amount of lead detected in samples versus typical consumer exposure.”

Asked about these concerns, city spokesman Jason Lorenz offered the following email reply: “While I cannot directly respond to Mr. Del Toral's remarks without first contacting the EPA Region 5 office, I can say that the City of Flint follows all the testing procedures and schedules as required by the U.S. EPA.”

He added that the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) endorses the city’s sampling method. The MDEQ did not respond to phone calls and e-mails seeking its comments on the controversy.

Del Toral contended in an interview that what Flint’s doing is actually exploiting a “loophole” in the law.

“From a technical standpoint, there’s no justification for the way Flint is conducting its tests,” Del Toral said. “Any credible scientist will tell you [the city’s] method is not the way to catch worst-case conditions.”

There is no legitimate reason for the city’s methodology, said Del Toral.

EPA rules, he said, required that such interviews be routed through the agency’s public affairs people. But he was willing to speak out nonetheless, he said, because of the potential harm to the public.

FLUSHING OUT REAL ANSWERS

It was Del Toral who, after determining that the lead problem plaguing the Walters family was coming from outside their home, connected LeeAnne with Edwards at Virginia Tech.

Instead of taking a single sample after a line had been “pre-flushed” under the city’s direction, Edwards instructed Walters to collect a series of samples from water that had been allowed to sit in the service line long enough to accurately reflect levels the family could be exposed to under normal use.

(Meanwhile, that same service line, dug up and replaced after the sample collection, was found to be made of lead in one section and iron in another.)

Edwards tested the water and discovered that the lead contamination ranged from 200 ppb to the 13,200 ppb figure that stunned LeeAnne Walters—and should likewise shock many others.

Given the age of much of Flint’s infrastructure, Edwards agrees with Del Toral’s assessment that the test results they found at the Walters home amount to an alarm going off, and others in the city need to pay attention.

“I do not see any reason why there would not be serious problems occurring in at least some other Flint homes,” said Edwards.

In 1986, the U.S. Safe Drinking Water Act was amended to prohibit the use of lead pipes in public water systems. Every house built before that is potentially at risk, said Edwards. About half of Flint’s roughly 40,000 homes are at least 50 years old.

Making things worse is the fact that the high levels of chlorine being used to treat Flint’s dirty river water lead to the creation of a carcinogenic byproduct know as total trihalomethanes, or TTHM. To keep TTHM levels down, the city is adding ferric chloride. The trouble is, that additive can also accelerate the corrosion of lead and iron pipes.

Adding yet another layer to the problem is something the city is not doing.

According to Del Toral, Flint should be adding corrosion-control chemicals designed to help keep lead and copper in pipes from leaching into drinking water. Doing so is required by federal regulations, wrote Del Toral in his memo.

“To our knowledge, that is inaccurate,” said Flint spokesman Lorenz. “Before the plant was placed in operation, the City (and our engineering firm) had numerous discussions with DEQ personnel and inquired if corrosion-control chemicals – typically phosphates --needed to be included in the treatment process. The use of these chemicals was not required or mandated.”

What’s indisputable is this:

Flint’s water contained corrosion-control chemicals until April 2014, when Flint’s ties to the Detroit water system were severed. Flint officials hailed that changeover as a cost-cutting move for a city facing a financial crisis so severe it had been placed under the control of a state-appointed emergency manager.

Discontinuing the use of the anti-corrosion chemicals allowed toxic scale built up on the insides of pipes over the past decades to be released into water flowing into people’s homes, explained Del Toral.

In his memo, Del Toral warned: “The lack of mitigating treatment is especially concerning as the high lead levels [that result] will likely not be reflected in the City of Flint’s compliance samples due to sampling procedures used…”

In other words, at the same time the city is exacerbating the problem, it’s conducting tests that will probably fail to identify the true extent of the threat.

Del Toral described the situation as a “major concern.”

“In the absence of any corrosion control treatment, lead levels in drinking water can be expected to increase,” he warned in his memo.

The EPA offered Flint officials the use of agency experts to help get the situation under control, said Del Toral, but added that, to his knowledge, the city has so far declined all help.

LeeAnne Walters said that when she asked why city officials weren’t taking the EPA’s offer of assistance, she was told, “We don’t need it.”

Flint spokesman Lorenz, on the other hand, maintained that “the city continues to work closely with the MDEQ and the EPA Regional Office.”

As for Walters’s family, that the city has finally replaced the service line leading to their home, and lead levels have dropped below the 15 ppb EPA action level.

The problem now, she said, is that water currently coming out of her tap tinged yellow and smells of rotten eggs. City officials have given her no explanation as to the possible cause of that.

It is just one more in a long list of questions that need to be addressed.

“What we need,” said Walters, “are more answers.”

But it’s not just answers the people of Flint require.

They also need solutions. And, as Del Toral’s EPA memo emphasizes, they need them immediately.