In 2006 and 2011, the state legislature expanded the Sex Offender Registration Act (SORA), originally passed in 1994, creating harsher measures for registrants. The amendments retroactively made most registrants register for life and imposed geographic exclusion zones barring them from living, working, or spending time with their children in large areas of every city and town. Additionally, the legislature added extensive and onerous new in-person reporting requirements that make it a crime for registrants to borrow a car, travel for a week, or get a new email account without immediately notifying the police. The changes were imposed without due process or a mechanism for review or appeal for the vast majority of registrants.

The ACLU of Michigan and the University of Michigan Clinical Law Program brought the case in 2012. Last year the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals declared that portions of the law are unconstitutional and held that restrictions added to the law cannot be applied to people convicted before the changes went into effect. Noting the lack of evidence that registries actually do anything to protect the public, the Court held that Michigan cannot cast people out as “moral lepers” solely on the basis of a past offense without any determination that they actually present a risk to the community. The state appealed that ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. Learn more about the case.

BASIC FACTS

Michigan’s Registry Is Exceptionally Large

- Michigan’s registry is the fourth largest state registry in the country.

- As of May 2017, there were almost 43,000 people on Michigan’s registry.

- Michigan has the third highest per-capita registration rate of any state.

- Approximately 2,000 more people are added to the registry each year, or about five a day.

- Because the registry is so large, it hard for police to know which registrants need careful monitoring.

Michigan’s Registry Is Expensive

- Taxpayers pay between $1.2 - $1.5 million each year just on the registration database maintained by the state police’s central registration unit.

- But most of the costs of SORA fall on local police, the Department of Corrections, and the Michigan courts, who spend untold millions on registry enforcement each year, with no demonstrable public safety effect.

Michigan Registers People Who Are Not a Danger to the Community

- People are required to register without anyone ever deciding whether they are a danger to the public.

- Registration is based solely on past convictions (no matter how old), not on present risk.

- Modern research shows that scientific assessments are much better at predicting risk than past convictions.

- Some people with minor convictions can present significant risk while other people with what appear to be more serious convictions can present little risk.

- The registry includes children as young as 14.

- The registry includes people who never committed a sex offense.

- The registry includes people who were never convicted of a crime.

- Michigan requires most people to register for life, no matter how old their crime, what they have done since, or how small a risk they pose to the community.

SORA LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OVERVIEW

1994 SORA First Enacted:

- confidential, non-public, law enforcement database;

- no regular reporting requirements;

- revealing registry information is a crime & a tort (treble damages);

- 25 year inclusion in database, except repeat offenders;

- allowed limited public inspection of registry information.

1999 Amendments:

- created internet-accessible registry;

- required quarterly or annual in-person registration;

- required fingerprinting and photographs;

- increased penalties for SORA violations;

- expanded categories of people required to register.

2002 Amendments:

- added new in-person reporting for higher educational settings.

2004 Amendments:

- registrants’ photos posted on the internet;

- imposed registry fee, and made it a crime not to pay the fee.

2006 Amendments:

- criminalized working within 1,000 feet of a school:

- criminalized living within 1,000 feet of a school;

- criminalized “loitering” within 1,000 feet of a school;

- increased penalties;

- created public email notification system.

2011 Amendments:

- created federal SORNA-based 3-tier system;

- classified registrants retroactively into tiers based solely on offense;

- tier level determines length of registration and frequency of reporting;

- retroactively extended registration period to life for Tier III registrants;

- offense pre-dating registry results in registration if convicted of any new felony (“recapture” provision);

- in-person reporting for vast amount of information (like internet identifiers);

- “immediate” reporting for minor changes (like travel plans & email accounts).

2013 Amendments:

- imposed annual fee.

RECIDIVISM, RISK, AND REGISTRIES

Public Conviction-Based Registries Don’t Work

Public sex offender registries do not reduce sex offending or make the community any safer. In fact, the consensus of modern scientific research is that public registries do not reduce crime, and may actually increase sex offending.

Researchers believe this is so because public registration makes it harder for people to return to their families and communities, and harder for people to get schooling, housing, and jobs. All people with records, including individuals convicted of sex offenses, are less likely to recidivate when they have strong family and community support, stable housing, educational opportunities, and good jobs.

Most Child Sex Offenses Are Committed by Non-Registrants Who Know the Victim

About 93 percent of child sex abuse cases are committed by family members or acquaintances, not strangers. By far the greatest danger of sexual abuse of children is not from strangers, but rather from relatives, sitters, friends, etc.

While a Small Percentage of People Convicted of Sex Offenses Pose a Significant Risk to Public Safety, Most Do Not

About 95 percent of individuals arrested for sex offenses do not have a prior sex offense or are not on a registry. In other words, the great majority of sex crimes are committed by new offenders, not repeat offenders. The risk of a new (first) sex offense is about 3 percent in the general male population. The risk that someone will commit a new sex offense varies significantly among offenders. Most people convicted of sex offenses do not reoffend sexually.

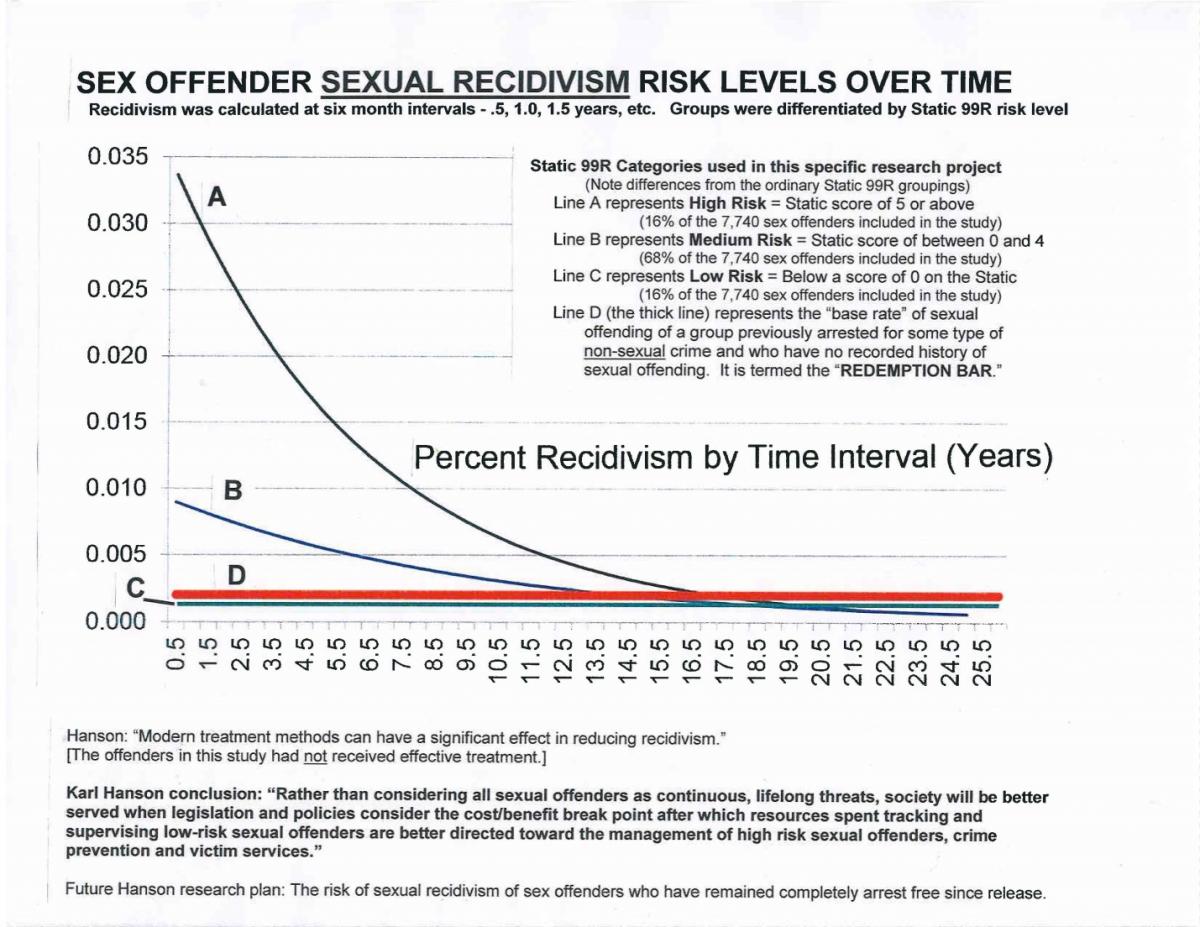

The Likelihood of Reoffending Drops Dramatically Over Time

From the outset, individuals who committed sex offenses and are considered low risk have a lower risk of committing a new sex offense than a baseline group of non-sex offenders. Even medium-to-high risk offenders become less likely to offend than the baseline over time. Individuals who reoffend usually do so within three-to-five years.

Experts have concluded that lifetime registration is unnecessary because after 17 years, reoffending is very unlikely, even for people who were originally high-risk offenders. The graph below shows how the recidivism rates of offenders at different risk levels compare to the baseline risk of non-sex offenders.

MICHIGAN’S EXCLUSION ZONES

- Registrants cannot live or work within 1,000 feet of a school.

- Registrants cannot “loiter” within 1.000 feet of a school, which means that registrant-parents cannot participate in many of their children’s educational activities, attend school activities, or take their children to a park within an exclusion zone.

- School exclusions zones apply to all registrants, even to those whose crime had nothing to do with children and who have never been found to be a danger to children.

- The consensus among scientific researchers/Social science research shows no connection between where child sex offenses occur and where the offender lives or works.

- Most child sex offenses occur in the home and are committed by family members, friends, sitters, or others with a connection to the child.

- Exclusions zones don’t work because they block registrants from housing, employment, treatment, stability, and supportive networks they need to build and maintain successful, law-abiding lives.

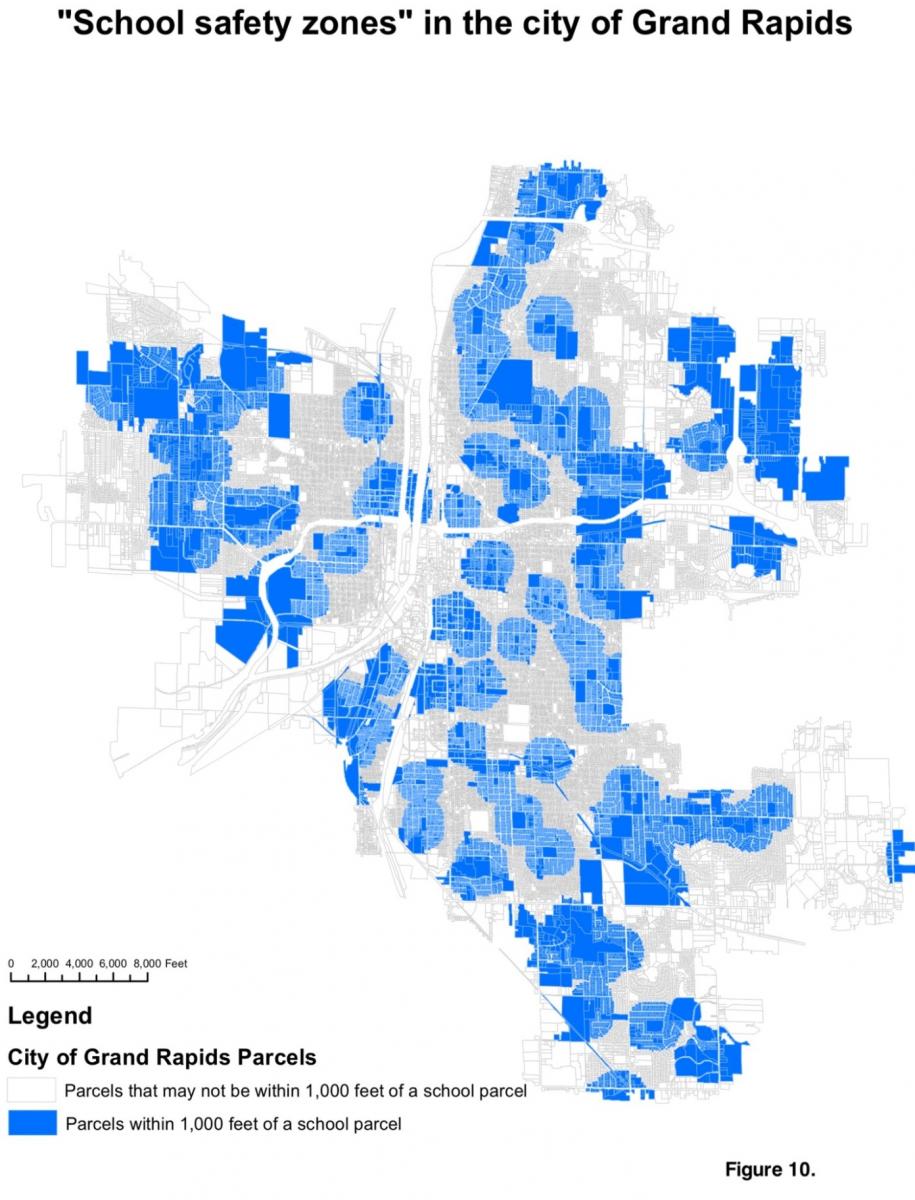

- A study by the Prison Policy Initiative found that almost 50 percent of Grand Rapids is off-limits to registrants (and much of the other 50 percent contains non-residential areas). See the map below.

The U.S. Department of Justice recommends against offender exclusion zones because the zones do not reduce crime:

“Restrictions that prevent convicted sex offenders from living near schools, daycare centers, and other places where children congregate have generally had no deterrent effect on sexual reoffending, particularly against children. In fact, studies have revealed that proximity to schools and other places where children congregate had little relation to where offenders met child victims.”

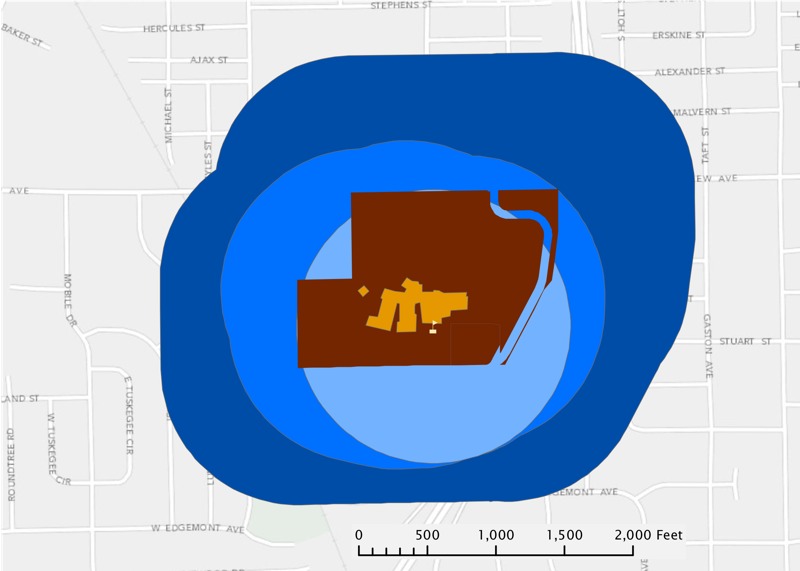

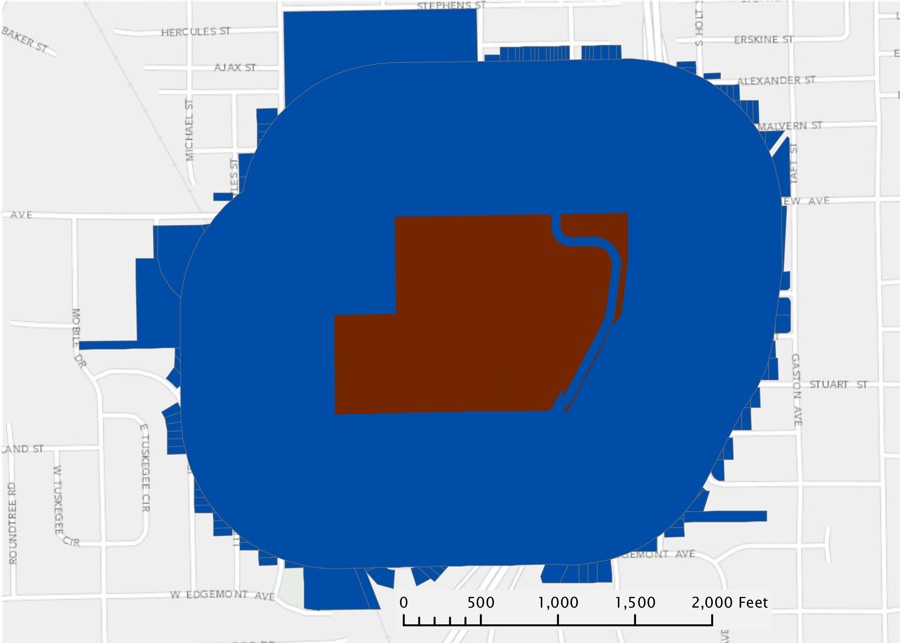

A Department of Justice-funded study found that exclusion zones may have increased recidivism in Michigan. It is also impossible to know where exclusion zones are because the size and shape of the zone depends on whether you measure from the school door, the school building, or the school property line. As the image below shows, the size and shape of exclusion zones depends on how you measure them. Because registrants and law enforcement officials have no way of knowing where property lines are, they cannot know where exclusion zones begin and end. This is why the federal district court held the exclusion zones to be unconstitutionally vague.

Changing Exclusion Zones Depending on How You Measure

1000-foot geographic zones drawn around each of three nested protected areas: the school’s entrance (school symbol), the school building (orange) and the school property (brown).

Actual geographic zone measured from school building perimeter to home property line.