Growing up in a working-class Detroit household, Marilyn Kelly originally set her career sights on teaching, earning a BA from Eastern Michigan University and a master’s degree from Middlebury College in Vermont. While still in her 20s, Ms. Kelly won election to the State Board of Education and then began pursuing a law degree. Attending Wayne State University School of Law in the 1960s, she was just one of six women in her class. Elected to the Michigan Court of Appeals in 1988 and the Michigan Supreme Court in 1996, she became Chief Justice 13 years later, holding the position until 2010.

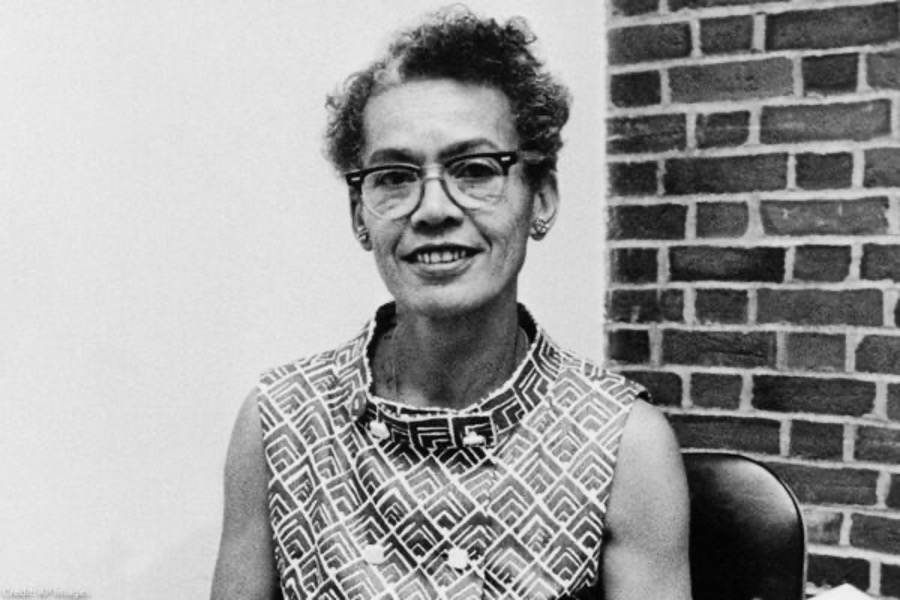

Included among her many honors is a lifetime achievement award from the ACLU of Michigan. The Detroit and Michigan Chapter of the National Lawyers Guild has honored her for a "life dedicated to justice and equality” and Michigan Lawyers Weekly named her "Woman of the Year” in 2012. Now the Distinguished Jurist in Residence at the Wayne State University Law School, she recently talked with us about her personal journey, the state of the women’s movement, her admiration for Madam C.J. Walker and more as part of our Women’s History Month activities.

Q: As a young person, what did you see as the horizons open to you?

A: The horizons were not high. Most women in my generation were told they should be homemakers and mothers. If they wanted to work outside the home, they might want to be a teacher, secretary, nurse or an airline stewardess. That was about it. In high school, when I was given vocational counseling, I was never urged to look into anything else. In fact, I was discouraged from considering any other profession. And that was typical at that time.

Q: Did that limit your dreams?

A: It definitely limited my dreams. I had always been enthralled by books of adventurous travel . Books about going to the arctic or into the jungle. Things like that. But women didn’t seem to get to do those things, and it seemed so unfair to me. Then, when I was maybe 15 or 16, I read an autobiography written by a woman marine biologist named Eugenie Clark, who was able to go scuba diving in all these places around the world to study marine life. I thought it was the most exciting thing I’d ever heard of. Eugenie got her first big job when she was hired by an employer in some far-off place who mistook her name for Eugene and thought he was hiring a man. When she arrived, he realized his mistake, but it was too late. And that is how she got her foot in the door.

Q: So, you initially went into teaching because that was one of the few options you thought was available to you?

A: Teaching did interest me, but it wasn’t my first choice. And, ultimately, I couldn’t see spending my entire life doing that. So, I began looking for other things.

Q: How did you end up going to law school and becoming a lawyer?

A: I sort of stumbled into that. When I was in my 20s, President Kennedy had been assassinated, but his words were still ringing in my ears: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country." So, I got active in the local political party in Albion, where I was teaching. Then a new state Constitution was adopted that, among other things, expanded the number of people serving on the state Board of Education, and I thought, “Why not me?” So, I ran and, much to the consternation of the editors at the Grand Rapids Press, I was elected to a statewide office at the age of 26. That certainly shaped my future. I began learning about the law because of the legal issues we were dealing with as a board. And I started thinking how really interesting the law was, which led me to decide to leave teaching and go to law school. It wasn’t a planned thing.

Q: Do you consider yourself a feminist?

A: Yes

Q: How would you define that?

A: I view myself as a human being on par with other human beings, male or female, and that gender shouldn’t determine my destiny. I also believe that in our society women have been discriminated against, and that discrimination has to be ended.

Q: When you went to law school at Wayne State University, there were only six women in your class. Did you feel like you were discriminated against?

A: Not while in law school. I was well-treated there. In fact, that’s one of the reasons I’m teaching there now – to give back to the university. But when I got into the legal profession, I definitely ran into discrimination. There were almost no women judges, and few women advocates. The women licensed to practice law back then were mostly relegated to work that took place behind the scenes. They did important work, but that work was not recognized. Women lawyers did not receive the same pay as men, and weren’t elevated to partnerships the way men were in the large and important law firms. There were few role models back then, and that made it harder for us to succeed, because we didn’t know how to pattern our behavior.

Men weren’t accustomed to women being their peers, or their superiors. For many men, that was a very difficult concept.

Q: How would you describe the state of the women’s movement today?

A: Things have changed greatly. Teaching at the law school, I have an opportunity to get to know young women who are becoming lawyers, and I see the jobs that are available to them, the partnerships available to them at the large firms. They feel empowered to take chances regarding what they do professionally. They feel they need to be respected, and that their views deserve to be heard. They expect to be treated as equals, and are willing to fight for that. And they’re going out into a world where men are more accustomed to working with women. That all represents a very large change. The atmosphere today is much better than what I experienced 50 years ago.

Q: What about for Black women and other women of color?

A: I think the situation for them remains discouraging. I’ve seen how much more difficult it is for them to advance professionally than it now is for white women. Their plight is different, obviously, because they must deal with racism as well as sexism. And changing that, with white women joining in solidarity, remains the next frontier in the women’s movement.

Q: Any recommendations regarding what people should be looking at during Women’s History Month?

A: One woman who’s an incredible inspiration is Madam C.J. Walker, an entrepreneur, activist and philanthropist who was born on a plantation in the 1860s and went on to become the first Black woman to be a millionaire. There are several good documentaries that tell her story. There’s also a dramatized series about her life, titled Self Made, that people can also watch.

Q: Is there anything we haven’t touched on that you’d like to express?

A: I’d like to say it is a good thing that we are celebrating Women’s History Month. It’s appropriate. This battle for women’s equality isn’t totally won. It is necessary for men and women alike to learn from history, and to see what women have been able to overcome to this point, and to understand the challenges that remain for women – all women – to be treated the same as men.

Date

Monday, March 28, 2022 - 2:00pmFeatured image