For more than 30 years, Grand Rapids, Michigan police have engaged in the egregious, unconstitutional practice of detaining people on the street and then fingerprinting and photographing anyone who isn’t carrying an ID, all without a warrant. In the process, they have disproportionately targeted Black people, young people, and lower-income people. The Michigan Supreme Court will soon hear an ACLU case challenging the practice, and the court’s decision will have a lasting impact on police practices and the right to privacy in Michigan and across the nation.

The case centers around two Black teens, Keyon Harrison and Denishio Johnson, who were detained, fingerprinted, and photographed by Grand Rapids police in 2011 and 2012, but were never charged with a crime. Yet their fingerprints and photos remain in a police database to this day, where they can be searched at will. This is a serious violation of privacy and the exact type of unconstitutional search the Fourth Amendment protects against.

Keyon was just 16 years old when police detained him as he walked home from school in May 2012. After Keyon helped a classmate carry a toy fire truck to his internship site, Keyon was stopped by Grand Rapids Police Captain Curt VanderKooi, who found Keyon’s actions “suspicious.” VanderKooi searched Keyon’s backpack, another officer questioned his classmate, and Keyon was peppered with questions about his actions, but no evidence was found that he had done anything wrong. Despite that, because Keyon didn’t have an ID on him, the officers fingerprinted and photographed him. His fingerprints and image remain in a police database.

Denishio, then 15 years old, was similarly detained, fingerprinted, and photographed by a Grand Rapids police officer in 2011 while he was taking a shortcut through the parking lot of an athletic club. There had been car break-ins reported at the parking lot months earlier, but Denishio did not match the description of the suspect. Still, he was handcuffed and fingerprinted, despite officers confirming he had no outstanding warrants or previous arrests. He was released after his mother confirmed his identity.

Neither Keyon nor Denishio were charged with a crime, and both cooperated with the officers’ questions. There was little reason for them to be stopped in the first place, and even less of a reason for their fingerprints and photographs to be added to a flawed police database of people stopped without identification.

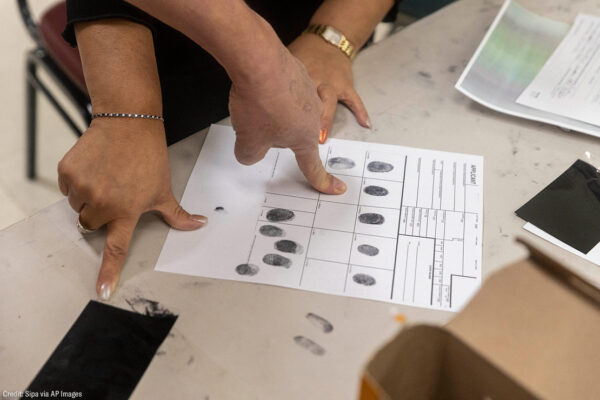

Grand Rapids police have subjected thousands of people to unconstitutional searches and seizures solely because they were not carrying an ID. In Keyon and Denishio‘s cases, lower courts ruled that fingerprinting people does not constitute a search under the Fourth Amendment, and therefore no search warrant is required to take fingerprints from people on the street. But as the ACLU argues in the brief we filed today with the Michigan Supreme Court, fingerprinting is a Fourth Amendment search both because it involves officers physically intruding upon people’s bodies for the purpose of obtaining information about them, and because it violates people’s reasonable expectation of privacy against forced collection of the unique biometric identifiers contained in their fingerprints. And because fingerprinting people during police encounters on the street does not fall into any recognized exception to the Fourth Amendment’s bedrock requirement of a warrant, the fingerprinting policy violates the Constitution.

Not only does the Grand Rapids “photograph and print” policy violate the Fourth Amendment, it also encourages racial profiling and undermines community trust. A review of 439 stops under this policy from 2011 and 2012 found that 75 percent of the people stopped by police were Black, while just 15 percent were white. This is a huge disparity from the city’s overall racial makeup, which is 21 percent Black and 65 percent white.

The unconstitutional fingerprinting program widens the disparities even further, particularly for young people of color who are less likely to be carrying an ID because they aren’t old enough to drive, can’t afford an ID, or rely on public transit and so have no need for one. Subjecting these young people to unconstitutional fingerprinting and storing their identifying data in a police database is stigmatizing and increases the chances of police interactions in the future. As we have seen repeatedly, a simple interaction with law enforcement on the street can turn deadly for Black and Brown people. We need to reduce interactions with law enforcement, not enable police to gather even more information about people during often harassing stops on the street.

The Michigan Supreme Court can put a stop to these unconstitutional practices once and for all. If police have probable cause for an arrest, they have long been able to capture fingerprints as part of the post-arrest booking process. But allowing police to compel a person to provide fingerprints while going about their business on the street puts people at the mercy of police whims whenever officers wish to gather this sort of sensitive biometric information, for any reason or no reason at all.

While police took Keyon and Denishio’s fingerprints using ink and paper, powerful new technologies like mobile fingerprint and iris scanners threaten to digitize these abusive police practices and make it even easier for law enforcement to collect and share our sensitive biometric identifiers.

No state requires its residents to carry an ID when they leave their front door. But if the court greenlights Grand Rapids’ practice, there will be nothing stopping police from forcing people to choose between their right to walk around without ID, and their fear having their fingerprints taken, saved, and exploited. We can’t let Black and Brown people bear the brunt of the next generation of police abuse — we need the courts to step in and strike down this dangerous policy.