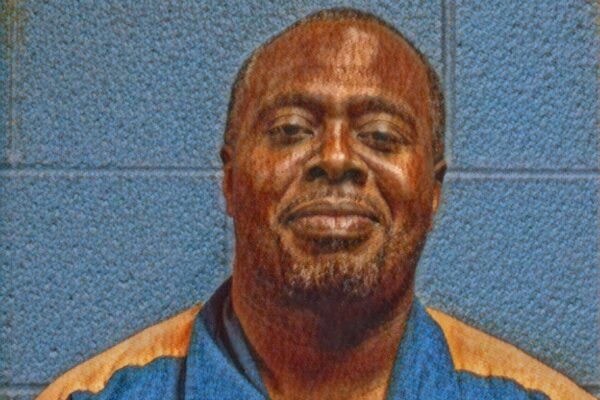

The odds were stacked against James Adrian from the time he was a child.

With a father who was not around and a single mom who struggled with drugs, food was scarce and moves were frequent. He switched schools eight times in 12 years. Though bright, with no stability at home he struggled in school. A test he took while in the 8th grade showed his spelling and language skills were at an elementary school level. One of the few men in his life was a grandfather who, according to court documents, was a “drug kingpin” who exposed Mr. Adrian to that dark world at an early age.

Living in the notoriously dangerous Ypsilanti housing complex known as Liberty Square, he grew up living in fear. Guns, drugs and robberies were commonplace. A cousin recalled him “hiding in his bedroom for weeks at a time, afraid to come out.”

Battling what was later diagnosed as depression, he began using alcohol and marijuana at age 12. There was a suicide attempt. Eventually, he began running with a bad crowd.

Given all that, it is not surprising that Mr. Adrian ended up in prison at the age of 17, sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for his role in a killing that occurred when an attempted robbery went awry. After a night of drinking and drug use, an older man convinced him to assist in an armed robbery. When the intended victim fled, fatal shots were fired. As a kid facing murder charges with no adults to provide guidance, Mr. Adrian declined a plea bargain that would have spared him a life in prison. Had he accepted that offer, he would be free today.

Instead, he is one of more than 700 people housed at western Michigan’s G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility diagnosed with the COVID-19 virus.

He is also, like a vastly disproportionate number of people locked in Michigan Department of Corrections facilities, a Black man. As with so many aspects of this pandemic, which continues to expose inequities throughout society, the racism embedded in our criminal legal system is being brought to the fore. Given that Black people are imprisoned at nearly seven times the rate of white people in Michigan, the impact of the deadly virus on this population is especially devasting to a population attempting to survive in an environment that is far beyond high-risk.

According to analysis done by the Marshall Project, the COVID-19 death rate for people imprisoned by the MDOC is nearly 200 percent higher than it is for the state as a whole.

That grim statistic is part of an explosion of cases in many Michigan prisons since the pandemic’s outbreak. Before that, though, there was great hope on Mr. Adrian’s horizon.

As the result of successful court challenges to reactionary laws like the one that allowed 17-year-old James Adrian to be locked away for life, he was able to go before a judge and, with the help of attorneys, made the case that he had reformed, and is no longer a danger to society. Much evidence supported that claim.

As a still rebellious teenager, he had difficulty adjusting to prison, racking up a string of misconduct violations during his early years behind bars. But as time wore on, and he grew into a man, Mr. Adrian began the process of reform, eventually becoming a model prisoner.

“The thing that sparked my change was the last time I went to segregation for fighting in 2007,” he recalls. “My aunt told me that I was fighting to stay in, while my family was fighting to get me out. I just realized I had to make better choices with my life and grow up. I was living with no hope of freedom, so I just strengthened my faith and was motivated by the rising sun.”

Making the most of the opportunities available to him, he pursued an education, so far making the dean’s list six times as he works his way toward a college diploma. He has also become a published poet and essayist. Instead of getting into trouble, he is now, at 42, a mentor to younger inmates, and a prison community leader, playing a lead role in an effort that has significantly reduced violence inside the prison. He credits behavior modification and rehabilitation classes for helping him learn how to change.

And he has expressed sincere remorse to the family of his victim.

“I’m not the same person now that I was at the age of 17,” he says.

At last report, he was surviving being stricken by the COVID-19 virus. But he knows that can change at any moment. Based on the new sentence handed down by a judge in 2018, without intervention by the governor, the earliest he can be released in 2024.

“Now I’m wondering if I will make it that long,” he says