Stories from a broken bail system

The cost of a broken bail system isn't just monetary — it is crushingly human. Below are the stories of people whose lives have been impacted by bail, or witnessed bail's devastating effects on others' lives.

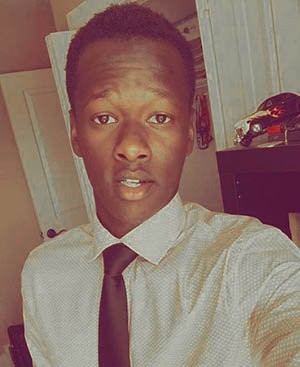

Djibril Niyomugabo

For Grand Rapids attorney H. James Telman, Djibril Niyomugabo was much more than a former client. Although he’d represented Djibril when the teenager had two minor scrapes with the law, Mr. Telman saw the Rwandan refugee with an unsettled homelife as someone in need of a friend and mentor.

A devout Christian, Mr. Telman taught the boy scripture in sabbath school class. As a basketball coach, he showed Djibril how to set picks and make lay-ups. And as a mentor, he provided the him with guidance when needed, and a place to live for six months when he had no place else to turn.

“He was a good kid,” Mr. Telman says. “There were issues at home, but he was a good kid.”

Now, Djibril is dead.

In 2016, at the age of 18, Djibril was arrested for allegedly smashing a car window and breaking a bottle of pricey wine he’d found inside. Unable to afford the $200 bail required for his release, Djibril sat behind bars for three days before committing suicide, hanging himself in a Kent County jail cell.

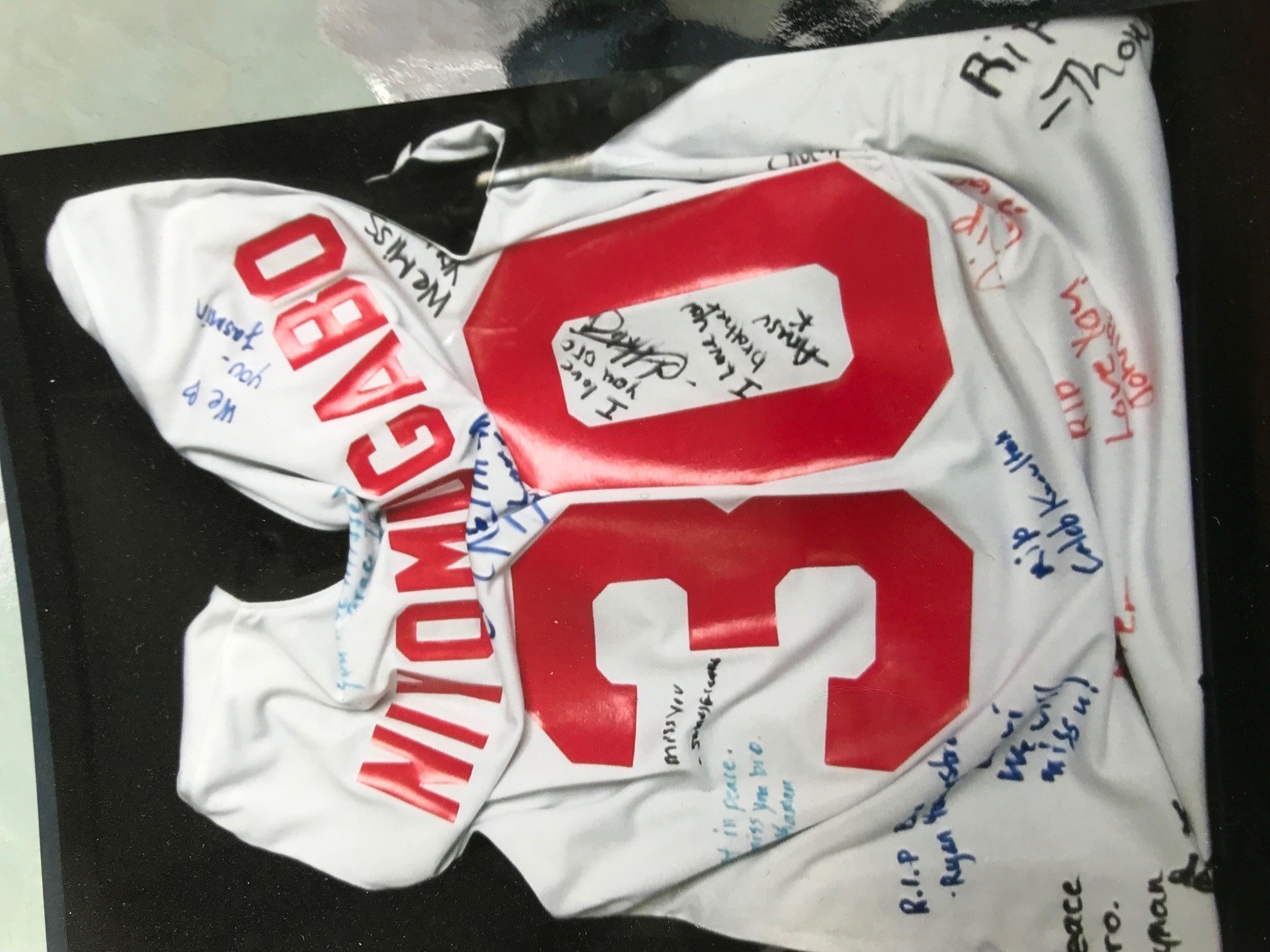

Djibril Niyomugabo's basketball jersey signed with messages from his teammates. It was hung at his funeral.

Saying he is a firm believer that people who commit crimes should “get what they deserve,” Mr. Telman just as firmly believes that there is no way justice is served by having someone who is not a flight risk and is accused of committing a non-violent crime sit in jail simply because they are too poor to make bail.

The way Mr. Telman sees it, the lack of $200 cost Djibril his life.

“I think there’s no question he’d still be alive if he hadn’t been forced to stay in that jail cell for three days,” Mr. Telman says. “I think he was probably despondent, and feeling like a screw-up. Given the circumstances, I don’t know that I’d be able to stand it if something like that happened to me at that age. As they say, ‘There but for the grace of God go you or I.’

Azairian Cartman

Azairian Cartman’s future looked bright. As a 24-year-old African-American student at Northern Michigan University, he eagerly anticipated spending a semester studying abroad in Morocco in 2017 before finishing his studies and getting a bachelor’s degree. A member of the Army Reserves with no criminal record, he’d already applied to become a police officer in his hometown of Chicago.

Then two scrapes with the law that ended with him sitting in jail because he couldn’t afford the bail imposed on him seriously derailed all his plans. Two women he’d been involved with accused Mr. Cartman of stealing from them. One claimed he stole $150; the other said he’d taken an Xbox. Complicating matters was the fact that one of the women claimed he threatened and abused her – the same claim she made when seeking a personal protection order against him that two other judges denied – showed up at a preliminary hearing and repeated her allegations, but offered no evidence. As a result, the judge increased his bond to $225,000, forcing Mr. Cartman to languish in jail for six months while awaiting trial. He lost his job and apartment, had to drop out of school, and forfeited all the money paid toward his semester in Morocco, which he never got to do.

With his resources exhausted and eager to get on with his life, he took a deal that involved pleading guilty to one felony count of larceny. Significantly, with the support of the prosecutor, the judge agreed to expunge his record if he successfully completed one year of probation. Having done that, Azairian is trying to move forward. After a time being homeless, Mr. Cartman is living with his grandmother in Chicago and working toward getting a license to drive semitrucks. The plan is to pay off his bills and student loans, and then return to college and finish getting his degree. With a felony on his record, becoming a policeman is no longer an option.

“This whole thing has literally affected every aspect of my life,” he says. “I’m willing to speak out about it, because I don’t want what happened to me to happen to anyone else.”

Jessica Preston

Jessica Preston was eight months pregnant when she was arrested in Macomb County for driving with a suspended license in March 2016. It wasn’t her first run-in with the law, but it was her first driving-related offense.

That didn’t matter. She was given a choice: Spend 14 days in jail while waiting for a hearing date or come up with $10,000. Too poor to make bail, she was put behind bars. Five days after being jailed, what was already considered a high-risk pregnancy became infinitely riskier when she went into labor while locked behind bars. Ignoring her repeated claims that she was going into labor, jail personnel refused to call an ambulance, until it was too late to move her. Instead, she was forced to give birth on a mat placed on what’s been described as a “filthy” jail house floor.

Mother and child survived the ordeal. But the trauma remains, prompting lawyers for Ms. Preston to file a federal civil rights lawsuit on her behalf, claiming her constitutional right to humane treatment was violated.

A longtime addict prior to her child’s delivery, Ms. Preston had a history of drug arrests and outstanding warrants for failure to appear in court. If she were rich, Ms. Preston would have been allowed to purchase her freedom while awaiting trial. But because she’s poor, her life was put at risk and her son has the Macomb County Jail listed as the place of his birth on his birth certificate.

Speaking to a reporter about the horror she experienced, and her reason for speaking out, Ms. Preston has said, “I would never want it happening to anyone ever again."

Noting the need to reform Michigan’s bail system, Ms. Preston’s attorney, Harold Perakis of the firm Ihrie O'Brien, equates his client’s situation to that of people previously sentenced to jail terms in Macomb County and other parts of the state because they couldn’t afford to pay the fines imposed after being convicted of minor crimes. Calling what’s known as “pay or stay” policies unconstitutional, the ACLU of Michigan previously filed a lawsuit intended to halt that practice.

Keeping poor people accused of minor, non-violent offences locked up because they can’t afford bail is really no different, says Mr. Perakis. “The same concept that makes ‘pay or stay’ policies unconstitutional should also apply to bond issues. Everyone needs to have their right to due process protected.”

Richard Griffin

Richard J. Griffin knows firsthand how quickly even just a few days in jail can throw a person’s life into a downward spiral.

In February, Mr. Griffin, 27, was arrested for having a handgun in his car after being pulled over by Detroit police outside what he later learned was a drug house. Mr. Griffin says he's not a user. Instead, he was there as a favor, picking up someone he knew in need of a ride. The cops checked his license and found an outstanding warrant for an unpaid $63 traffic ticket that Mr. Griffin mistakenly thought had been paid years ago. ought had been paid off. Taking those two factors into account, his bail was set at $850 – even though, other than traffic violations, he had no criminal history. During his video arraignment, he was instructed by guards at the jail to not ask questions of the magistrate. No attorney was available to explain his rights or argue on his behalf.

“Essentially,” Mr. Griffin explains, “they were just trying to move people through the process as fast as possible.”

His mother, fiancée and fiancée’s mother were able to pool resources and come up with the money, but he had to sit in jail for two days while the whole process ran its course.

Those few days, as is the case for many people being held in pre-trial detention, proved to be critical.

Out of work since November 2018, Mr. Griffin had finally landed a new job as a customer service representative for a rental business. He was supposed to begin work the day following his arrest. Without access to a phone -- the police had seized it as evidence, and he still does not have it back -- he was unable to call his new employer and explain why he was a no-show his first day on the job.

Not surprisingly, the job was no longer there when he was released.

Because he was unemployed for so long, Mr. Griffin had fallen behind on his rent. To keep from losing his apartment, he had scheduled an appointment with a social service agency that provides emergency assistance. Instead of showing up for the meeting, he was sitting in jail. As a result, no aid was obtained, resulting in his eviction. He’s now living at the home of his fiancée’s mother.

Despite having his life start heading downhill so quickly, Mr. Griffin says he feels relatively lucky. Even a few days of sleeping on a thin mat thrown on a cold cement down on the floor and being given food that’s barely edible can be an unnerving experience. He’s thankful to have had someone to reach out to in a time of great need.

“I had people close to me who were willing to come up with the money and bail me out,” he explains. “But when I was in jail, I saw people all around me who didn’t have anyone they could turn to. So, they had to stay locked up.”

The way he sees it, the current system is highly punitive, even for those who’ve done nothing wrong.

“This was really an eye-opening experience,” says Mr. Griffin. “Instead of treating people as if they are innocent, you are automatically treated like you are guilty. If you have the money to pay what they are asking for, you get to go free. But if you can’t pay, then you can’t go free. How is that fair?”

Starmanie Jackson

Starmanie Jackson spent a week in the Wayne County Jail because she couldn’t come up with $700 to pay her bail following her arrest for a traffic stop and a three-year old warrant for an alleged felony. It was the first time the 24-year-old single mother of two had been behind bars. It was also the first time she had been separated from her daughters, who are just 3 and 5 years old.

“Now I know why some people commit suicide in jail,” she says. “You feel so desperate.”

Taken into custody following a traffic stop in Macomb County on April 8, Ms. Jackson was transferred to a lockup in Detroit when the warrant showed up on her record. Appearing before two different magistrates on two different days—neither of whom allowed her to ask questions—in just minutes they set her bail at $700, failing to ask if she could afford it, which is required by law. The law also requires that judges and magistrates determine if a person is a danger to the public or a flight risk when setting bail. They failed to do this as well. Ms. Jackson also did not have an attorney appointed to represent her, which is mandatory when a person cannot afford legal representation. “I had questions I wanted to ask, but was told not to speak,” she says.

The $700 bail Ms. Jackson was required to pay to go free was insurmountable as she has a hard time making ends meet even under the best of circumstances. Ms. Jackson is a Certified Nursing Assistant, and at the time was between jobs. In fact, she was about to begin her new job on the day of her arrest, but because she was in jail and couldn’t afford the exorbitant phone rates charged prisoners, she couldn’t call her employer to explain her absence.

Ms. Jackson’s family turned to a bail bond company which agreed to pay her bail, on the condition that Ms. Jackson pay $315 to the bond company—money that would never be returned no matter what happened in her case. Unable to come up with even the $315, Ms. Jackson sat in a cell while her close-knit family frantically tried to raise the money to bail her out. Meanwhile, Ms. Jackson sat in jail where she was given food infested with maggots and had to use sanitary napkins to dry off after showering because towels weren’t available. No toiletries were handed out. Adding to the stress of confinement in what she says were filthy conditions were guards who showed open contempt for the prisoners. “You ask questions,” Ms. Jackson says, “and they just brush you off like you’re some sort of disease.”

As for the $165 a day it costs Wayne County to keep people like Ms. Jackson locked up, she notes, “Taxpayers are paying a lot of money to keep people who aren’t dangerous in a jail with terrible conditions and food that is unfit to eat.”

While locked up, the godmother of Ms. Jackson’s children, Hillary Oliver, cared for her kids.

“They were kicking, screaming, yelling ‘I want my mommy,’” says Ms. Oliver.

On top of trying to care for two traumatized children, Ms. Oliver and others repeatedly reached out to other family members in attempt to raise the money to get Ms. Jackson out.

“Because it wasn’t the first of the month, no one had even $20 to spare,” explains Ms. Oliver. “It was a really big struggle.”

Ms. Jackson says waiting to go free was emotionally devastating, as she shed weight unable to stomach food crawling with insect larvae. She says she broke down, sobbing uncontrollably at least twice during her week of incarceration. Determined to help others avoid the trauma and humiliation she experienced behind bars because she was too poor to afford bail, Ms. Jackson agreed to be a plaintiff in a federal class-action lawsuit the ACLU of Michigan brought against judges and magistrates in Detroit’s 36th District Court and Wayne County Sheriff Benny Napoleon. The intent is to ensure that people such as Ms. Jackson have their constitutional right to due process and equal treatment protected from the moment they first step before a magistrate. This includes judges and magistrates appointing an attorney to those who cannot afford one, asking about a person’s ability to pay bail, reviewing evidence to determine if they are an unmanageable flight risk or danger, and considering other non-financial release conditions that might otherwise minimize any such risks.

“I’m not doing this for me,” she says. “I’m doing it for the people coming after me, because I don’t want them to have to go through what I just experienced.”

Ms. Jackson understands how people who’ve never been in jail might have misconceptions about what it is like. Until recently, she was one of those people.

“Before getting locked up, I thought jail would be organized, the food would be at least edible, and the treatment of prisoners decent,” says Ms. Jackson, 24. “I was wrong about all of that. I was treated worse than a dog. It was really an eye-opening experience.”

Keith Wood

Keith Wood was exercising what he believes is his right to free speech when he was arrested for passing out fliers on the public sidewalk in front of the Mecosta County courthouse in November of 2015.

Mr. Wood, 42, is a proponent of something known as jury nullification, and was trying to spread the word. The idea is that jurors who think a person might be guilty of a crime, but disagree with the law allegedly being broke, should know that they have the option of voting not guilty. Having done nothing more than that, Mr. Wood was arrested and charged with both jury tampering, a misdemeanor, and felony obstruction of justice.

Except for a driving violation that resulted in his arrest when he was 20, Mr. Wood has always been a law-abiding citizen. With no record of violence in his past, a family to support and a business to run, and strong ties to his community, there was no reason to believe this father of eight would cause any harm to others or flee to avoid prosecution.

But the magistrate setting bail treated Mr. Wood as if he were a hardened criminal who might skip town, setting his bond at $150,000 and requiring $15,000 up front for him to be released pending trial. Luckily, with a good credit rating and a high-limit card, Mr. Wood was able to come up with the money needed to gain his freedom.

In that respect, his case is different than the situation faced by many others who must sit in jail for weeks or months while they await trial because they don’t have the resources to pay their bail and go free, even though they’ve been convicted of nothing.

What his case does represent, though, is the unpredictable, potentially punitive nature of Michigan’s bail system. The way Mr. Wood sees it, the court was using an exorbitant bail amount to send Mr. Wood a message.

“There is no doubt in my mind that my bail was set so high as a way to try and punish me for doing something they didn’t like,” he says. “This was done because they didn’t like me exercising my right to free speech, and they were sending me that message.”

That, of course, is not supposed to be why bail is imposed. Having a lawyer present at his arraignment, to inform him of his rights and to make the case to the magistrate that Mr. Wood was neither a flight risk nor a danger, could likely have produced a different outcome.

Unlike a lot of people, Mr. Wood was able to borrow enough money to buy his freedom. But even a few hours behind bars is an unnerving experience.

“When you have the full force of government coming down on you to take away your liberty, even if it is just for a short time, is a very scary thing,” says Mr. Wood.

Convicted of the original charges, Mr. Wood – whose position regarding his actions and constitutionally protected free speech is supported by the ACLU of Michigan – continues to fight the decision, and is currently trying to get the Michigan Supreme Court to review his case.

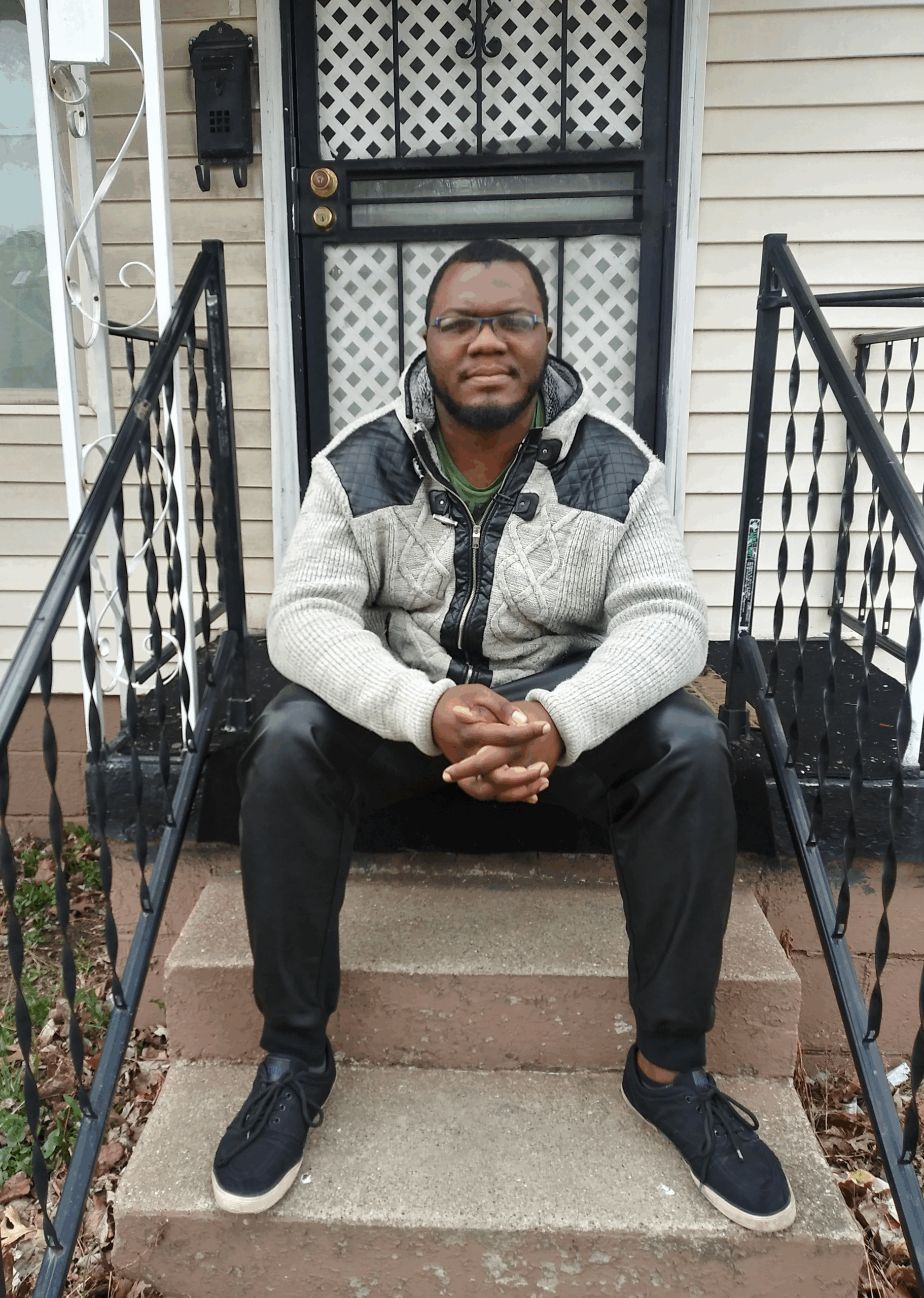

Zavon Washington

Tall and broad-shouldered, native Detroiter Zavon Washington is big enough that he didn’t have to worry about getting hassled by other prisoners when locked up in the Wayne County jail, but that didn’t prevent his recent week in jail from being a “horrible” experience.

“I can handle myself,” says the 27-year-old laborer and welder. “Even so, being locked up like that was still horrible. Your privacy is violated. You are strip-searched. The whole dynamic is designed to break you down. Being in there like that really messes with your mind. It was really a lot worse than I imagined. It is something you never want to come back to.”

A combination of unpaid traffic tickets and bail imposed by a magistrate meant that Mr. Washington had to come up with $2,800 to obtain his freedom. Money the father of two young children didn’t have. Money his family members didn’t have, either. As he says, “They got their own bills to pay.”

Arrested on a domestic violence charge that was later dropped, Washington’s only previous encounters with the police involved a dozen traffic violations stretching back several years. As the fines and late fees mounted, he continued to fall behind. But the situation only got worse sitting in jail, unable to work.

“I lost the job I had, which set me back pretty bad,” says Mr. Washington.

Were the issue bail alone, he could have borrowed the money from family because he only needed to come up with 10 percent of the $1,000 bond. It was the total amount being demanded by the court that kept him sitting behind bars. If not for the Detroit Justice Center and its partnership with The Bail Project, a nonprofit organization that provides up to $5,000 to get people out of jail while they await trial, Mr. Washington says he’d likely still be locked up, unable to work and falling even further behind.

“What they did for me, coming up with that $2,800 so that I could get out, that was a real blessing, and I’m really grateful for the help they gave me,” says Mr. Washington.

The money will be repaid and funneled back into helping others. But Mr. Washington is also helping pay it forward by speaking out about his case, and spreading the word about how harmful even a few days in jail can be.

“I want to make a difference,” he says. “People need to know how bad jail is, because anybody can end up in that situation.”

Martell Gresham

At 33 years old, Detroit resident Martell Gresham has spent most of the past 15 years in prison. He’s previously been convicted of stealing cars, operating a chop shop, and being a felon in possession of a weapon.

Mr. Gresham doesn’t shy away from that past.

“Whatever I did, I did,” he says.

But he also points out, and the public record confirms, what he didn’t ever do: commit a violent crime, or flee to avoid prosecution.

Given that, he’s understandably perplexed as to why a magistrate imposed $500,000 bail on him when Mr. Gresham was accused of being a felon in possession of a weapon following his arrest by Livonia police in February.

“Where’d they get that number from?” he asks, referring to the exorbitant amount of bail, which is only supposed to be used to ensure a person charged with a crime returns to court for trial, or in cases where violence is a concern. “How am I supposed to be a flight risk if I never ran before? How am I supposed to be a threat to the community when I never hurt no one before?”

What makes Mr. Gresham’s case particularly compelling is his claim that he suffered a mild stroke shortly after being jailed and being denied access to his medications. (He says he has suffered two previous strokes and has a prescription for aspirin, which is used in some cases as a blood thinner to help prevent strokes.) He can’t produce any records to verify that because, he says, those documents remain in the possession of the Wayne County Jail. What he does have is a letter from St. Mary Mercy Livonia hospital asking him to fill out a survey evaluating his stay there. According to the letter, he was discharged on Feb. 5, 2018 – four days after his arrest.

Clearly, something serious enough to warrant hospitalization occurred after he was locked up.

Following his release from the hospital, Mr. Gresham says he spent more than a month in the overflow ward of the Wayne County Jail infirmary, confined to a wheel chair without access to any physical therapy, or even a shower. He remained locked up until mid-March.

What changed was Mr. Gresham’s appearance before a different court. The original $500,000 cash bail, imposed by a magistrate in Livonia, was impossible to meet – even though court rules require that bail be set at an amount defendants can afford. “I could sell every single thing I own and not come close to coming up with that much money,” he says.

Six weeks after his arrest, with the help of a court-appointed attorney who wasn’t present at his arraignment when the original bail was set, Mr. Gresham’s bail was reduced to a $5,000 bond that required a 10 percent payment of just $500 for him to be released.

To help protect the rights of defendants such as Mr. Gresham, the ACLU of Michigan recently filed federal class-action lawsuit against Detroit’s 36th District Court seeking, among other things, a guarantee that defenses will be present when bail is first being sent.

Although he is still facing trial on the weapon charge, and the prospect of being sent back to prison if convicted, Mr. Gresham, who started a security business following his last release from prison and is doing volunteer work to help his community, is willing to talk about his bail experience because he sees a system in dire need of reform.

“Somebody needs to speak up,” he explains. “Because change has to be made. That’s all that matters.”

Stories of People Who Witnessed Bail's Devastating Effects on Others' Lives

Daisy Benavides

Daisy Benavides is a criminal defense attorney based in Grand Rapids. This is what she has to say about the current bail system and how it negatively affects her ability to represent her clients:

“Mounting a vigorous defense is much more difficult when a client is unable to get out on bail and has to sit in jail awaiting trial. Access is restricted to a limited number of hours, lack of privacy is a concern, and, in cases with voluminous files, making sure all the necessary documents are on hand is a challenge. Whether a defendant has easy access to the proper clothes, and how they appear in general, also makes a difference in terms of how they are perceived by a jury. So, in that respect, someone is much better off if they are able to come to court from home rather than coming from a cell escorted by sheriff deputies.”

“Beyond that, people who are able to remain free while awaiting trial can continue working, making sure they can support their families, keep their housing and transportation, and pay for their legal defense.”

“Finally, I have seen how people forced to sit in jail for months at a time because they can’t afford bail can be coerced into accepting a plea deal, even if they are not guilty of the crime they are accused of committing, because they are so eager to get their freedom back they will admit guilt just to get out.”

Frederik Stig-Nielsen

Frederik Stig-Nielsen is a criminal defense attorney based in Benzonia, near Traverse City. Regarding the current bail system and its effects, Mr. Stig-Nielsen says:

“I’ve had several clients sit in jail for more than a year while awaiting trial, only because they could not afford to post bail. Bail amounts are inflated because crimes are overcharged. Then they are elevated by overblown, ‘worst-case-scenario’ pretenses of community protection unrelated to the facts of the case and exaggerations about the accused’s background. The deprivation of attainable bail has ripple effects: defendants cannot actively participate in the preparation of their defense; they cannot work to contribute financially to their defense; and they often lose their jobs and homes and are estranged from loved ones. The general public doesn’t realize that people often plead guilty just so they can be done with it, just to get out of jail and get on with their lives. It is as my boss often says: ‘in this country you are presumed guilty until you purchase your innocence.’”

JOIN THE SMART JUSTICE CAMPAIGN LAUNCH

Related Content

We Sued to End the Evils of Cash Bail in Michigan